A Beloved but Unfinished Film

For over thirty years, "Hook" has persisted in a rare and enduring way. Many discover it as children, drift away from it, and then return to it much later, almost by surprise. This return is far from a simple rewatch; it feels more like a silent confrontation with who we once were. Its imagery, John Williams’ score, and a pervasive melancholy reactivate memories that seem to belong as much to our own history as to the film itself.

Over time, what once appeared to be a classic adventure reveals a much more fragile substance. "Hook" ceases to be a tale of pirates and fairies and becomes a reflection on absence, emotional distance, and the loss of one's internal landmarks. Yet, this richness is accompanied by a persistent sense of incompleteness. The film establishes profound emotional stakes, but some are never given the necessary space to fully unfold.

"Hook" does not leave the impression of a failure, but rather of a work constrained by its own limits. It touches, in flashes, upon something deeply human without ever being fully permitted to follow that path to its end. This perhaps explains why, even today, it continues to haunt us.

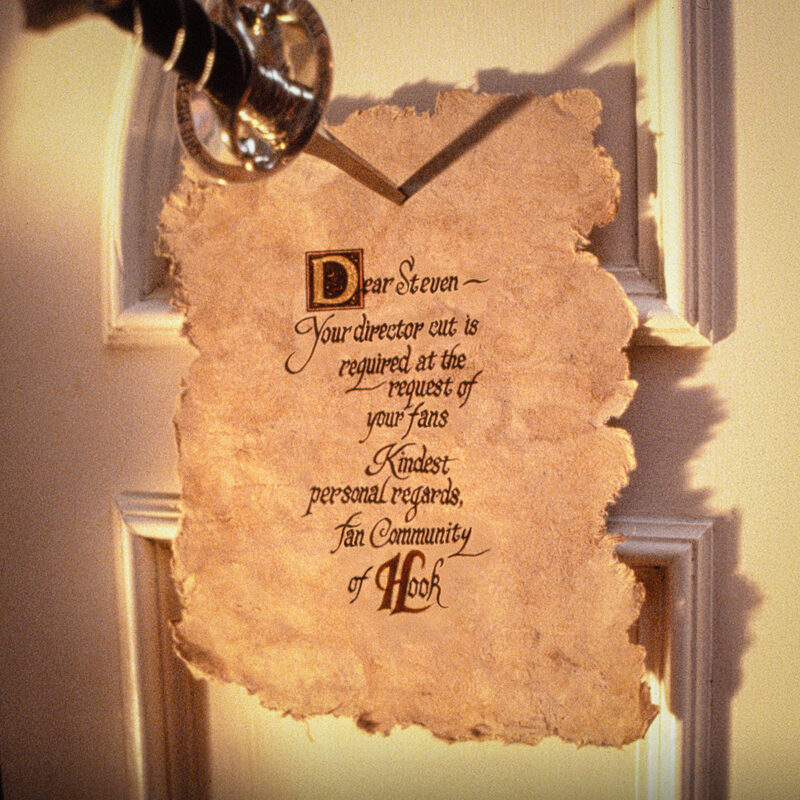

It’s worth noting that a longer version of "Hook" once existed. Just before it hit theaters, an extended cut was completed and screened for the public in Dallas in November 1991. This confirms that the movie we know today is the result of major last-minute edits, rather than being the film’s original intended form. Here is what this version makes visible.

The scenes we’re about to discuss were indeed filmed and are sitting in a vault somewhere. A complete version of "Hook" is possible provided that some time and energy are put into it.

“Hook is not a fairy tale. Hook is a movie about the practical reality juxtaposed against a world that is very famous from Peter Pan. But it’s really a story about a man who has to remember who he was, who has forgotten who he once was. It’s a huge Technicolor tale about amnesia, and getting your memory back. And therefore getting your childhood back.”

What is Hook Truly About?

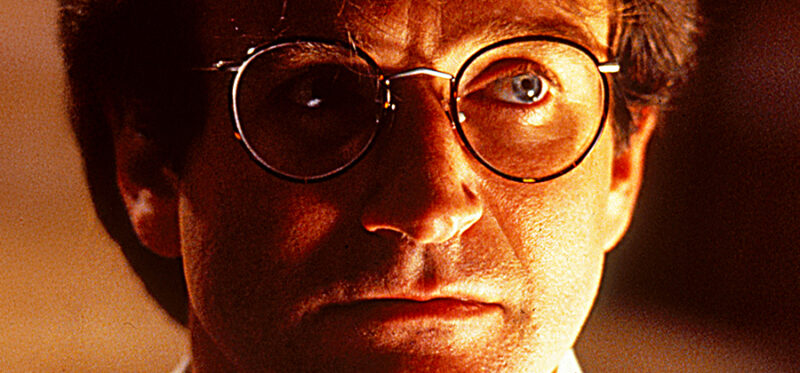

This statement by Spielberg is rarely used to discuss the film. Yet, it remains the most precise key to understanding "Hook". It forces a radical shift in how we view the movie. "Hook" is not merely a fable about growing up, nor a simple meditation on parental responsibility or the loss of innocence. It is a much more unsettling narrative: that of a man struck by psychic amnesia, who has, consciously or unconsciously, chosen forgetfulness as a survival mechanism in the face of trauma.

The dominant reading of "Hook" often reduces the film to a relatively classic moral: as we grow up, we forget the child we once were, and we must learn to balance maturity with imagination. This interpretation, while appealing, misses what Spielberg and the shooting script explicitly establish.

In "Hook", Peter Banning is not an adult who has "moved on" from childhood. He is a man who no longer remembers. A distinction to be taken into account. Here, forgetting is not a natural effect of time or responsibility; it is a crisis, defined in the script as amnesia, and treated as such within the film's dramatic structure.

Regression Leads to Redemption

The original script for "Hook" rests on a clear foundation: regression is not a failure, but a necessary step toward healing. Peter Banning can only rebuild himself by regressing, that is, by allowing the buried, repressed, and denied child to resurface.

In this logic, regression is never initially voluntary. It manifests through fits of anger, disproportionate emotional reactions, and a momentary loss of rational control, all typical signs of unresolved trauma. Peter does not "play" at becoming a child again; he is overtaken by something he tried to bury.

The film’s second act is therefore not a quest for learning, but a process of remembrance. The primary objective is not to defeat "Hook", but to defeat amnesia.

"Hook" exists in the juxtaposition of this amnesia with the myth of Peter Pan. Neverland is not presented as a simple fairy-tale world contrasted with adult grayness. It is a profoundly theatrical, artificial, almost "staged" space that functions as a psychic projection. Spielberg highlights this sense of artifice by beginning the film with a play where the pulleys and strings are hiding in plain sight, grounding the story in a world of performance. The characters act like children in a collective game. It is not a lost paradise, but a mental space: a theater of memory.

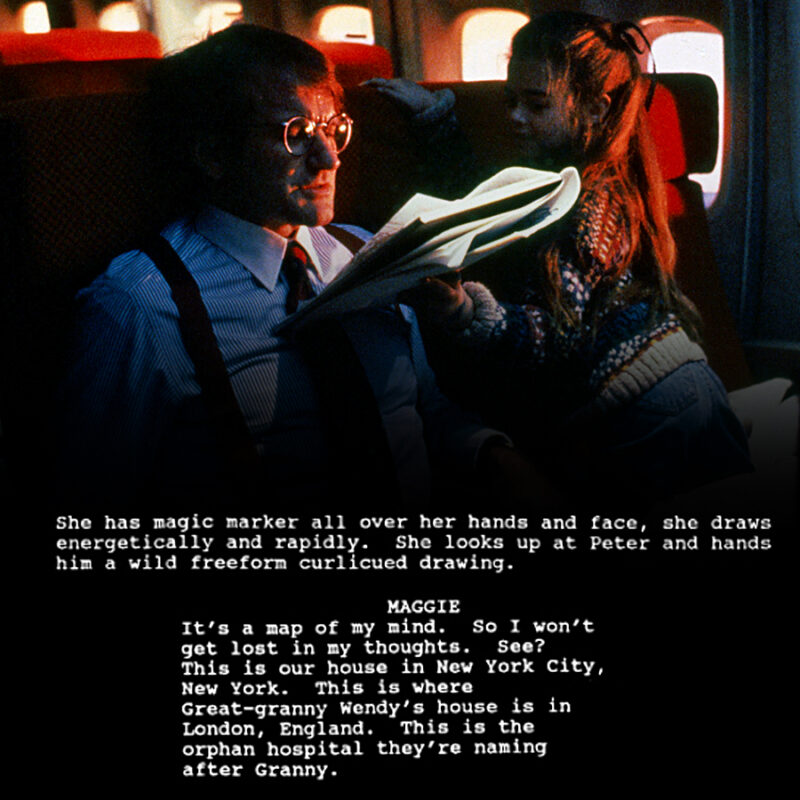

This reading is explicitly formulated in the original script. The flight to London gives Maggie an essential conceptual role: she explains to Peter her own way of working on memory by drawing a map of her mind. Imagination is not presented as an escape, but as a tool for mental structuring. This idea is extended visually by aerial shots of Neverland, which reveal a compass buried deep in the ocean, indicating the true nature of the island: not a geographical location, but the map of an internal, buried space to be rediscovered. This motif of the map permeates even the film's marketing. The teaser trailer relies on a journey through the exploration of a map, while the main poster is framed by scales and measurement markings inspired by ancient maps.

This is precisely why Peter Banning is initially unable to act within it. Spielberg describes him as "a man without imagination." In other words: a man who can no longer suspend his disbelief, a condition indispensable for accessing fiction and, by extension, his own past.

What "Hook" suggests, subtly but insistently, is that Peter’s amnesia is not merely suffered; it is also a form of protection. To forget Peter Pan is to forget a past laden with loss, rupture, and abandonment. Becoming Peter Banning, an obsessive corporate lawyer, is a way to take refuge in control, rationality, and measurable time, everything that childhood and the imaginary threaten.

The central conflict is thus not between the adult and the child, but between memory and repression. It is only by agreeing to revisit the trauma, symbolized by the return to Neverland, that Peter can free himself from the amnesia he imposed upon himself.

The theatrical release significantly softens this reading. By refocusing the narrative on the father-son conflict, it shifts the stakes from psychic territory to a more familial and emotionally accessible one. This choice, made late in the process, masks the coherence and radicalism of the initial project.

Nevertheless, traces of this intention remain. They explain the persistent unease that "Hook" provokes: a film often perceived as "flawed" or "unbalanced," when it is actually the vestige of a project far darker and more complex than its reputation suggests.

"Hook" is not a lesson on the necessity of growing up without forgetting one's inner child. It is a story about traumatic amnesia, the price of forgetting, and the difficulty, which can be terrifying, of remembering. By juxtaposing this issue with the tale of Peter Pan, Spielberg does not offer a simple nostalgic reimagining, but a meditation on memory, fiction, and the vital need to believe in order to survive.

Characters Deprived of Their Full Impact

In "Hook", Peter’s kids aren’t just there to be rescued or to give the hero a reason to fight. They are much more than plot points. Jack and Maggie are like two sides of Peter’s own fractured soul, each dealing with their father’s emotional absence in a different way. Through them, the movie takes Peter’s internal mess, his struggle between forgetting who he was and trying to remember, and makes it real.

Jack is the side of Peter that is starving for validation and a sense of place. When your dad is physically in the room but his mind is always at the office, you start looking for a father figure anywhere you can find one. His connection to Captain Hook isn't just about being tricked. Hook actually offers him something Peter doesn't. He listens to his anger, validates his hurt, and makes him feel like he finally matters. Through Jack, the film shows how a kid’s desperate need to be seen can make them turn their back on their own roots just to feel significant.

Maggie is the complete opposite. She is the part of Peter that refuses to let go of the light. She uses her imagination not to escape, but to stay grounded in what is true. Right from the start, she realizes the real villain in Neverland isn't a pirate with a steel hand, it is the act of forgetting. While Jack is tempted by a new life and a new uniform, Maggie treats memory like a lifeline. She knows, almost by instinct, that losing your history is the same thing as losing yourself.

This tension between the two children is where the heart of the movie lives. They represent two ways of handling a wound. You either give in to a new, cold reality that erases your past, or you fight to keep your empathy and your memories alive. As long as the movie focuses on both of them, the story feels balanced because it mirrors exactly what is happening inside Peter.

But as the film moves toward the big finale, that balance starts to wobble. Jack’s story stays front and center, but Maggie’s voice starts to get drowned out. Even though she carries the most important themes of the movie, she gets pushed to the sidelines. When her perspective fades, a huge part of Peter’s internal struggle effectively goes quiet.

That shift leaves a mark on the ending. Without Maggie’s journey being fully realized, the film’s message about memory and emotional healing feels a bit thin. The counterweight to Hook’s influence is gone, leaving a gap where a powerful resolution should have been.

In the end, Peter’s children are deeper characters than the movie ultimately allows them to be. By holding them back, "Hook" shows its own cracks. It is a film with a beautiful, profound vision that just couldn't quite follow through on everything it promised, leaving its most important emotional anchors a little bit adrift.

Compassion as a Forgotten Force

Maggie’s gradual disappearance from the spotlight is especially heartbreaking when you look at the role she was supposed to play among the Lost Boys. In a more complete version of the story, she isn't just another kid waiting for her dad to show up. She becomes a steady, protective force for the boys held captive by Hook. In a place like Neverland, where your memories are constantly slipping away, Maggie brings a sense of stability through simple acts of care and attention.

Her role is practical and grounded. While everyone else is caught up in the drama, Maggie is the one who actually acts. She doesn't give the Lost Boys orders or make grand promises. Instead, she listens to them. She reminds them of something they’ve completely forgotten, which is the simple warmth of being loved by a parent. In a world run by ego, cruel games, and manipulation, her quiet presence is actually a powerful form of resistance.

The contrast here is everything. Captain Hook rules through fear and mind games. His power depends on making people forget who they are so he can dominate them. Maggie, on the other hand, doesn't care about authority. She isn't looking to control anyone, she just wants to connect. Through her, the movie hints at a beautiful idea: that true freedom doesn't come from winning a fight, but from the ability to see someone’s pain and respond with kindness.

In this sense, Maggie becomes more than just a child. She is the one fixed point in a world designed to keep you lost. While Neverland pushes fear and forgetting, she brings back gentleness and memory. She doesn't offer a way out through strength, but through something much deeper: the acknowledgement of suffering. By talking about love and home, she wakes up buried memories in the Lost Boys, creating a safe space where they can finally feel what they’ve lost. She doesn't erase their wounds, she just lets them be real.

This all connects to the bigger theme of motherhood and the emotional threads that tie generations together. Maggie is the natural successor to Wendy and Moira. She is that presence that holds everything together, balancing imagination with reality and the past with the present. Through her empathy, she jumpstarts the memory of love in the Lost Boys, and symbolically in Peter himself. She represents exactly what Peter was missing and what he has to learn to value again if he ever wants to heal.

When this arc fades away, it does more than just hurt Maggie’s character development. It shifts the entire moral weight of the film. Without her gentle influence, Neverland risks becoming nothing more than a stage for spectacle and swordfights. The story loses that emotional depth where the inner conflict was meant to play out, leaving the film’s heart feeling just a little bit out of reach.

The Music That Speaks Without Words

The music in "Hook" is perhaps the clearest window we have into the movie that almost was. Even though it isn't a musical in the traditional sense, several songs were actually written before filming even started. While those songs never made it to the screen as full musical numbers, their melodies didn't just vanish. They stayed behind, woven deeply into the orchestral score, transformed into something more subtle.

These musical themes pop up at the most crucial times, usually during those quiet, private moments where the characters are just existing. They fill the silences and the long looks where something is shifting deep inside a character, even if the script doesn't spell it out. The music ends up carrying the weight of what the editing or the dialogue no longer has time for: the memory, the regret, and the flicker of hope.

Through these repeating melodies, the score hints at a version of the story where relationships were much more developed and the connections were more intimate. The music acts as an echo of scenes that aren't there anymore. It doesn't just "hit the beats" of the action; it adds layers of meaning. It reminds us that the real heart of the film isn't the big adventure, but how that adventure actually changes the people living through it.

In some scenes, the music even seems to push back against what we are seeing on screen. While the image might be leaning into a joke or a fast-paced chase, the score introduces a gentle, almost sad gravity. It acts like an invisible thread, keeping the characters tethered to their pasts, their wounds, and the things they truly want but can't always say.

In this way, the music is a silent witness to the film’s original soul. It preserves the structure of a story that was meant to be more contemplative and more focused on inner growth than grand spectacle. If you listen closely, you can hear the outline of a more reflective "Hook", a film that trusted quiet silences and restrained emotions just as much as it trusted big Hollywood magic.

This isn't just a theory, either. The release of the Ultimate Edition of the soundtrack, produced by Mike Matessino for La-La Land Records, really pulled back the curtain on this. It lets us hear the original songs and the preparatory work in a much more complete way. Having access to this material does more than just give us a great soundtrack to listen to. It gives us a concrete look at the film's original emotional blueprint, proving that the music wasn't just background noise. It was meant to be one of the main pillars holding the entire story together.

“Every movie I’ve ever made comes from a deep emotional place. Even the lighter, more playful ones come from pain." "Even Hook has a deeper meaning in my life.”

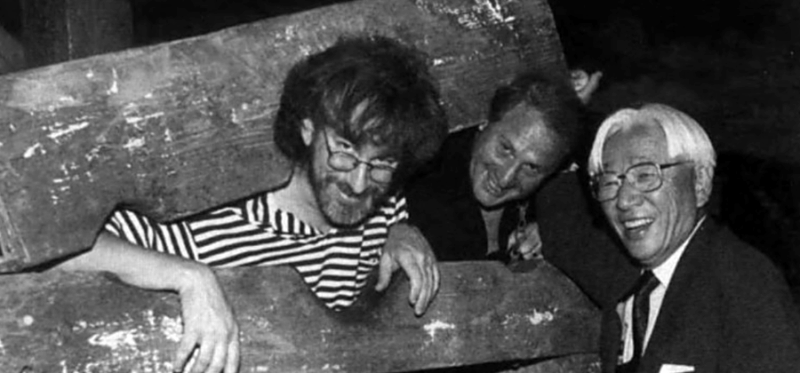

A Deeply Personal Film for Steven Spielberg

Beyond the plot of the movie and the symbolic elements of Peter Pan, "Hook" is actually one of Steven Spielberg’s most deeply personal works. He has said so himself many times, and you can feel that intimate connection running through every frame. Through James Hart’s script, Spielberg found a way to work through his own questions, his own old wounds, and the things he had kept quiet for years. Spielberg has always used cinema this way, but "Hook" concentrates these elements more than any of his other films. "Hook" isn't just a movie about a businessman trying to fix his work-life balance.

It hits much closer to home as an exploration of personal and family trauma. Spielberg has talked openly about how he spent a long time downplaying his Jewish identity, mostly out of a fear of being targeted or standing out. That choice was a survival tactic, a way of becoming partially "amnesiac" about his own history just to move forward. "Hook" puts that exact struggle on screen through Peter Banning. Peter has achieved massive success in the world, but he did it by erasing who he used to be and cutting himself off from his own memories.

Through Peter, Spielberg is essentially staging his own journey from avoidance to acceptance. Peter’s amnesia isn't an accident, it is an act of survival. He buried his past so he wouldn't have to carry the weight of it. As he slowly starts to remember, he isn't just "becoming a kid again," he is accepting a much bigger story that includes his heritage and the things that hurt him. The Banning family becomes a mirror for that internal tug-of-war between worldly success and being true to where you come from.

There are even specific moments in the film that hint at this deeper meaning. The ceremony honoring Wendy at the beginning of the movie feels like a deliberate nod to collective memory. The way it is filmed echoes real-life tributes to people like Nicholas Winton, who saved so many lives during the Holocaust. By creating that visual link, Spielberg is quietly signaling that "Hook" is about more than one man’s trauma. It is about the shared wounds of a community.

When you look at it this way, Neverland stops being just a fantasy playground and starts looking like occupied territory. It is a land taken over by an authoritarian force that has stripped away its freedom and its history. Peter’s return becomes a mission of liberation. It is the story of someone who left home, built a new life elsewhere, and finally has to go back to face the darkness he left behind.

Notice Peter’s flight path in the movie: he goes from the U.S. to London, then to Neverland. This isn't just a random trip, it mirrors the exact path taken by American soldiers in the '40s as they headed overseas to join the war effort in Europe.

In this context, Captain Hook turns into something much darker than just a theater villain or a flashy pirate.

For a long time, Hook has been driven by a thirst for revenge against Peter Pan that he just can't satisfy, leaving him trapped in a loop of endless fighting. In Hook, he stands as an idol to his crew, building a cult of personality that feels like the world’s most infamous dictatorships. He controls people by playing on their wounds, the ones you can see and the ones hidden inside. His main symbol, the hook itself, is the physical proof of one of his main traumas. He considers his crew as a professional army. He keeps them in constant training for one final war, a war he claims will end all others. He convinces them that beating Peter Pan is their only way to be saved. Their village lives on a culture of constant violence, where injuries aren't meant to be healed anymore but are shown off like trophies. Hook uses Jack’s own pain to manipulate him into becoming a pirate. This is exactly how authoritarian regimes operate: leaders mobilize the masses by turning shared trauma and hatred into the main driving force.

We are talking here about the representation of the pirates on a symbolic level. The violence of the pirates in the film is mostly transformed into commercial behavior; they are constantly trying to sell and bargain. This is expressed through the abundance of prices and shop signs that fill the Pirate Town. As soon as we see the pirates, they are bargaining: for a treasure map, a wooden leg, a fish, eyepatches, cigars, and so on. They even fight simply because one refuses to buy the other’s trinket.

It is a society built on a model of authoritarian capitalism, where threats and oppression guide every interaction.

Standing against him, the Lost Boys represent a very different kind of resistance. On the surface, they seem to live in total chaos and instability. But their world is built on values that are the polar opposite of Hook’s. While the pirate demands total submission to his authority, the Lost Boys operate as a community. Their apparent messiness actually hides a more organic, almost democratic way of living. When Rufio calls for a vote and asks everyone to make a choice, the movie is saying something profound: even in a broken world, freedom starts with the ability to decide things together.

This clash between tyranny and collective choice gives Neverland a whole new layer of depth. Saving this world isn't just about killing the bad guy in a swordfight. It is about restoring a place where people can speak freely, remember their past, and make their own decisions again. Neverland is only truly "free" when the people living there can finally reclaim their own stories and their own lives.

I felt like a fish out of water making Hook. I didn’t have confidence in the script. I had confidence in the first act, and I had confidence in the epilogue. I didn’t have confidence in the body of it. I didn’t quite know what I was doing, and I tried to paint over my insecurity with production value, the more insecure I felt about it, the bigger and more colourful the sets became.

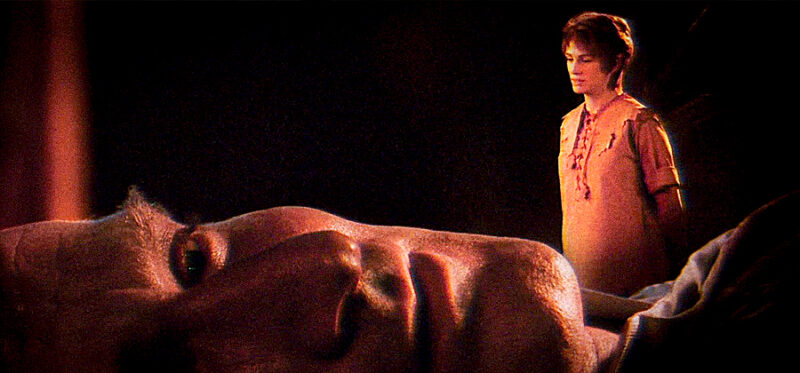

In this light, the character of Tootles becomes incredibly moving. He is no mere eccentric; he is a survivor, perhaps even a refugee, defined by a loss he could never move past. Where Peter Banning chose amnesia as a shield, Tootles has forgotten nothing. He exists in a raw state of permanent survival, haunted by the clarity of what was taken from him. He lives in a state of constant fear, visibly terrified by the pirates' kidnapping of the children, an event that resonates violently with his own past trauma, keeping him in a state of total stagnation. His obsession with his marbles is far more than a simple fixation, they are not just toys, but the last physical link to everything he lost: his home, his safety, his identity, and the life he was supposed to have.

The green gas symbolizing the threat during the children's kidnapping is no coincidence.

When Peter returns from Neverland and hands the marbles back, the moment is transformative. Peter no longer looks at him with judgment or confusion, but with profound empathy. He finally recognizes the weight of Tootles’ internal exile. By returning them, Peter is not simply restoring a lost object; he is performing an act of true recognition. He says, without needing words: "I see your pain, and I understand what you lost."

That simple gesture is what allows Tootles to finally let go. He isn't "cured" of his loss, but because his pain is finally acknowledged, he is no longer a prisoner of it. His return journey to Neverland marks the true beginning of his healing. By recognizing the trauma that had marginalized him and condemned him to a state of constant fear, Peter finally offers him the opportunity to reclaim his inner self. For Tootles, Neverland is no longer an unreachable nostalgia; it becomes once again a habitable space. Tootles can return there freely, not to take refuge, but to reclaim the life that was torn away from him.

"Hook" belongs to the same lineage as the adventure films directed by Michael Curtiz and starring Errol Flynn. A notable influence is "The Sea Hawk", a classic film from the Golden Age of Hollywood who is an allegory for the European situation and the rise of German expansionism in 40's. James Hart’s script was already deeply shaped by this influence. The music used in the "Hook" trailer, as well as some of its temporary tracks, actually comes from Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s score for that film.

By weaving all of this into "Hook", Spielberg reveals a massive shift in how he tells stories. This film marks the moment he realized there is a history more serious and heavy than pure fantasy, a reality that can no longer be kept at arm's length. You can see this change starting to simmer in The "Color Purple" and "Empire of the Sun", but "Hook" is the crossroads.

Spielberg is no longer interested in making conventional family films or studio-driven blockbusters designed to meet industry expectations, with "Hook" and "Jurassic Park" standing as the last examples of that era. It leads directly to Schindler’s List, where Spielberg finally stops looking away and confronts the Holocaust head-on. Hook sits right in the middle: a film where the director tries to bridge the gap between childhood wonder and the deepest human questions, wrapping these heavy themes in a bright, colorful, and intentionally sweet spectacle.

Even with the constraints of a PG rating and the need for a family-friendly tone, Spielberg manages to maintain a sense of restraint in his depiction of violence, never compromising the narrative's core intent. With Hook, he found himself caught between his own symbolic vision and studio pressure to soften the raw, darker edges of Neverland. It becomes clear, then, why he appreciates the opening and the epilogue: these are the only moments where he could fully express his vision, free from aesthetic compromises.

Steven Spielberg initially tried to hand "Schindler’s List" off to other directors because he doubted his own legitimacy to adapt such a history. Hook became the vehicle through which he shared his own transformation. By walking in Peter Banning’s shoes and re-exploring his own story, he rediscovered what he had forgotten about himself. It was through this deeply personal process that he finally felt assured and fully legitimate to realize "Schindler’s List", having finally made peace with his own history.

“Children’s Theatre”: Spielberg’s Self-Critique of Hook

"Hook" was always a deeply personal project for Spielberg. He set out to make something truly moving and intimate, but the realities of production, especially the pressure to trim the runtime, kept him from fully realizing that vision. It was incredibly painful for him to have to cut twenty percent of the final edit. Even though the movie became a massive hit at the box office, it didn't feel like a win to him. In the end, he just wasn't able to make the film he had originally envisioned.

The Existence of a Longer Version

It is worth remembering that a longer, more complete version of "Hook" actually existed. Before it hit theaters, an extended cut was shown at a test screening in Dallas on November 9, 1991. This screening is proof that the movie wasn't always the version we know today. It was originally built to be something much more expansive.

Note that the test screening received a 96% approval rating from the audience who had the chance to experience it.

Reports suggest that the film was heavily edited down, mostly due to pressure over the running time. As a result, a huge amount of footage was left on the cutting room floor. Unfortunately, we still don't know exactly which deleted scenes were in that lost cut.

That early frustration for Spielberg was only made worse by the mixed reviews the film received back then. That initial backlash ended up trapping "Hook" in a bit of a box, labeling it as a disappointment and overshadowing the depth and ambition behind it. But over the years, the way we look at the movie has completely changed.

"Hook" has shown it has a rare power to stick with people across generations, sparking a level of love and reflection that few family adventures ever achieve. There is a lingering hope that, one day, Spielberg might look back on this film with a bit more peace. Perhaps he will eventually see that "Hook" wasn't a failure, but a deeply sincere and brave piece of work, one that was actually more successful than he ever gave himself credit for.

“I don’t have to keep studios happy. A long time ago I felt I did. I don’t feel that anymore. I don’t feel like I’m working for anybody but myself now.”

A Work That Deserves to Be Revisited

The fact that a much longer version of "Hook" once existed really changes how we look at the movie today. What we saw in theaters wasn't the final, polished vision of the filmmakers, but a tightened version that had to be squeezed into a specific box. Because of those cuts, the emotional balance of the whole story was shifted.

Looking back, it is much clearer that the parts of the film that feel a bit uneven or unfinished aren't there because of a lack of effort. They are the result of a forced compromise. The gaps in the plot and the characters who seem to disappear too quickly aren't mistakes in the script; they are the visible scars of a very difficult editing process.

Cinema history is full of movies that were only truly understood once people realized what happened behind the scenes. When we look at a film in light of what was taken out or compressed, the original heart of the story becomes much easier to see. Re-evaluating the movie this way isn't about trying to rewrite history, it is about finally understanding the film’s own internal logic.

"Hook" is the perfect example of this. Its emotional foundation is still there, and its vision is still powerful, even if some of it feels like a conversation that was cut short. Watching it today with the knowledge of what it was forced to become isn't just about nostalgia. It is about clearing away the fog. The film doesn't need to be changed, it just needs to be rebalanced so that the story it was trying to tell from the very beginning can finally be heard.

A Call to Rediscover Hook

This petition is, above all else, a respectful invitation to Steven Spielberg. It is an invitation to take a fresh look at "Hook" with the perspective and freedom that only time can provide. Now that the production deadlines, scheduling pressures, and box office expectations of 1991 have faded away, the film can finally be seen for what it is, away from the sense of urgency that shaped its birth.

This is not a demand to radically change the movie. "Hook" does not need to be reinvented. Instead, what we are suggesting is more like a work of refinement. It is about a new edit, a rebalancing of the rhythm, and a way to bring back elements that can restore the emotional heart of the story. Specifically, this approach could help bridge the gap between the movie’s second act and the intimate, thoughtful logic that was so carefully set up in the opening scenes.

Even small adjustments would be enough to let the film’s true message shine through. The goal isn't to add new meaning, but to let the meaning that is already there finally breathe. By giving more space to the silences, the shared looks, and the internal growth of the characters, the story could find a smoother emotional flow where every step of Peter’s journey feels like it truly belongs.

Allowing "Hook" to exist more fully would not mean rewriting its history or changing what it has meant to generations of fans. On the contrary, it would be an act of completion. It would be a way to honor a sincere and ambitious work by giving it the chance, at long last, to reach the form it was always meant to take.

Sign the Petition

This initiative isn't about criticizing or turning our backs on the movie we all grew up with. It is about so much more than just nostalgia or the warm memories I have of watching it as a kid. It actually comes from a deep, unshakable feeling that this story has so much more to give, a conviction that has only gotten stronger the more I’ve learned about the version of "Hook" that was originally supposed to be.

This is a heartfelt cry of love for the film "Hook". It has been unfairly criticized and too often dismissed. I believe it is legitimate to hope, even to plead, that it might one day exist in a complete and whole form, able to fully convey its message to the fans who love it and to those who will discover it in the future.

Next year marks the film’s 35th anniversary. And in a world where violence and threats seem to speak louder than compassion and understanding, what better moment to remind us of the values and the importance of memory, empathy, healing, and reconciliation, and to let them take their rightful place in the movie? If there was ever a time for "Hook" to be rediscovered, to breathe, and to mean something new, it is now.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this.

Please, Mr. Spielberg, release the director’s cut of Hook.

The petition is available at the following address: